Whig-Clio & Women’s History

08 Friday Mar 2013

Written by American Whig-Clio Society in Uncategorized

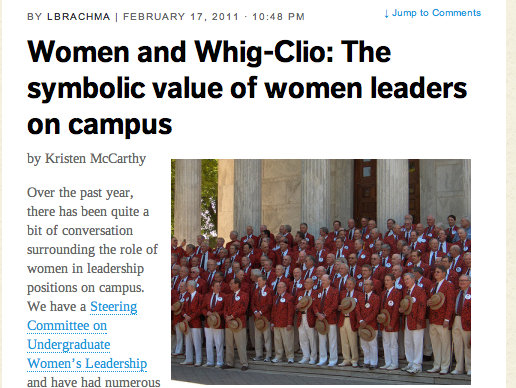

In February 2011, Whig-Clio Governing Council member Kristen McCarthy wrote a post on the blog Equal Writes, asserting that Whig-Clio’s lack of women in leadership positions represented a lack of appreciation for women’s voices in a prominent Princeton organization. McCarthy reflected that, “The dearth of woman leaders in Whig-Clio speaks to the problem of women not being vocal leaders on campus. Whig-Clio is the center of student voice on campus and, by choosing only men to lead; the Society is saying that we do not value women’s voices in political, literary, or philosophical debate.” As part of her post, McCarthy recounted an experience when she realized that, while in a room full of the twenty-one Whig-Clio officers, only three were women.

While three women may seem like a small number of leaders, to some Whig-Clio female alums, it represents substantial progress. Sue McSorley entered Princeton in the fall of 1973 and became involved with Whig-Clio when she went on a trip to Washington D.C. with a group of fellow students to meet with prominent political figures including George McGovern. As a student, she enjoyed the incredible speakers that Whig-Clio brought to campus and helped run a Model United Nations for high schoolers. When asked about what proportion of Whig-Clio leaders were female in her day, McSorley replied “You know at that time, whether there was a woman in a leadership position was not really all that relevant because there were so few women on campus…Think about it, there were 4400 undergraduates and 1100 or 1200 women…So we hadn’t reached a kind of critical mass yet where you would you know expect to find a woman in the leadership of every organization.”

Nevertheless, she did not feel discriminated against as a woman in Whig-Clio at the time. “I certainly didn’t feel unwelcome because I wouldn’t have done it if I felt unwelcome.” She thinks that this experience might have something to do with the type of women that flocked to Princeton’s campus after the university began admitting women in 1969: “One of the things that you have to connect when you’re thinking about these women and leadership is that…the people who applied to Princeton when they were high school students like me, the girls who applied either really wanted to go to a [formally] all male institution, they relished the challenge, they weren’t shrinking violets, they didn’t want to go on the well-trodden path, so we were a pretty assertive bunch of people.”

These early pioneers of coeducation were largely a product of the strong feminist movement in the 1960s and 1970s that McSorley found herself identifying with. “I was a very strong feminist. You have to understand, so I graduated from high school in June of 1973, Roe vs. Wade was decided in January of 1973. It wasn’t an issue for me in the sense that I cared a whole lot about abortion, it was an issue for me that I cared a lot about a whole bunch of men deciding things that would really only effect girls and women.”

Cara Eckholm

Nearly 40 years after McSorley first became an early female Whig-Clio member, Cara Eckholm began her time at Princeton. Eckholm joined the Princeton debate team as a freshman, and was appointed to the new position of the Director of Membership in the second term of her freshman year. She was convinced by friends to run for Whig-Clio president the following year and ended up winning the presidency.

“I think it’s totally changed my life,” Eckholm says of her experience with Whig-Clio. “I was really overwhelmed at first but it ended up being a really gratifying experience…I saw a lot of potential in the organization [and] ways to expand and we really did grow a ton in the past year or so. We doubled our membership and its been a really fun exciting project.”

While President, her administration tried to recruit more women members by hosting events that it thought would appeal particularly to women. “We tried last year hosting a couple of events we thought would particularly appeal to females…We did a series on authors that wrote biographies of famous women. So we had one about Cleopatra and then we had Bob Massey come too.”

The problem of the dearth of female membership, Eckholm thinks, is largely one drawn from other organizations. “I think a lot of it’s a product of the fact that a lot of Whig-Clio comes from the debate team and that tends to be very male-dominated and a lot of the subsidiaries are male-dominated, so its more a problem that’s stemming from our root organizations rather than the organization itself….They are plenty of women’s empowerment groups on campus that probably play a bit of a role but we’re kind of in competition with those groups. Like if someone joins Running Start instead of Whig-Clio then that detracts from female presence in our organization which actually has been sort of a problem for us…The type of female who would run for a position in Whig-Clio is the same type of female that would run for a position in those groups and once you commit to one thing you can’t do both.”

As far as being the female leader of a male-dominated organization, Eckholm rarely had problems. “Everyone’s been absolutely lovely. It’s definitely hard to control a room full of boys. I wasn’t the loudest in the group ever so there’s I guess struggles with that. But I’m sure if I was like a quiet male I’d be having the same problems.”

When asked what the biggest issue facing women today is, McSorley and Eckholm offered distinct perspectives.

As McSorley put it, “The kinds of things that occur to me first are not women’s issues, they’re family issues, they’re people issues…I think finding a way to be able to balance all of the things in your life that make your life meaningful is a challenge…It’s something that you have to be prepared to negotiate you know repeatedly in your life.”

Eckholm addressed the question with regard to the public perception of female leaders. “I think the biggest issue is, especially with women in politics, its very hard to run for office without giving out a perception that is going to alienate certain people. I know Hillary Clinton really had this problem. The first time she ran, I didn’t like her. And I felt like I was judging her for things that I would not be judging a male for but its so sort of subconscious that its hard to get over.”

On the bright side, Eckholm notes, “I think there are more women involved in Whig-Clio than women involved in politics generally.”

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts